“Orientation in space (and time) is the framework of cognition […] we take delight in physically distinctive, recognizable locales, and attach our feelings and meaning to them. They make us feel at home, grounded.”01 Kevin Lynch

The word orientation is derived from Latin oriens, meaning East. It stems from the mediaeval practice of drawing maps with East at the top. To find our orientation in space, we need to:

- find our position (the You-are-Here spot)

- and find our heading (the direction we are facing)

If we don’t achieve the first point, we feel lost. If we know our position, but not our heading, we are unable to proceed in any wayfinding task. Position and heading can only be found within a certain frame of reference. Interestingly, humans can switch easily between different frames of reference while navigating through space or while giving someone directions. In science different frames of reference are researched and many different terms are used. For design applications these three might be the most useful ones:

Egocentric frame of reference

This frame of reference places the subject in the center of the perceived surrounding. Therefore the egocentric frame of reference uses terms like left, right, front and back in connection to one’s own body. This feels rather natural to most of us—almost as everyone is imprinted with the practice of describing space in this kind of way. But surprisingly, there is a large of amount of people in the world who never use left or right to describe their surrounding!

Allocentric frame of reference

This frame of reference is independent from the subject and deals with the relation of the objects itself. We can say that something is in front of the court house or between the buildings. The objects and their positions form a relation and we can quickly construct a meaningful frame of reference for remembering theses positions or to give someone directions.

Geocentric frame of reference

This frame of reference is independent from the subject or the objects. It relates to coordinates outside of the objects. Cardinal directions are the most common use of a geocentric frame of reference. But they are by no means the only option. For example: if a region is situated between a mountain range and a shore line, it can be, that these landmarks become a much more useful reference system. People will then use equivalent terms to “to the mountains” and “to the sea” to describe directions.

In some parts of the world, the geocentric frame of reference is the dominant reference system02. People there have trained all their life to constantly keep their position according to the geocentric reference frame, even if they are indoors.

Orientation in the 21st century—the end of map reading as we know it?

The use of geocentrically aligned maps has been the wayfinding tool for centuries. But there is a paradigm shift taking place right now. Mobile navigation devices are not just digital maps. The dramatically change the way we move thru the environment. With their egocentric turn-by-turn navigation they usually lead us quicker and better to our target than ever before. But they do this without providing us full orientation. Like pocket calculators free us from doing mental arithmetic, mobile navigation devices take away the necessity to maintain a cognitive map of our environment. This is okay as long as the navigation devices work, but as soon as our devices run out of battery power, we are completely lost.

It is not unlikely that the current practice and ability of map reading will demise in the near future. Tourists with folding maps, standing at a street corner, figuring out their way to their next place of interest, will be a thing of the past. Egocentric devices and digital signs will lead the way—from one decision point to the next. Modern wayfinding systems should accommodate this paradigm shift. I believe they should allow to access their information from different frames of reference and provide orientation within a larger frame of reference along with egocentric turn-by-turn navigation steps.

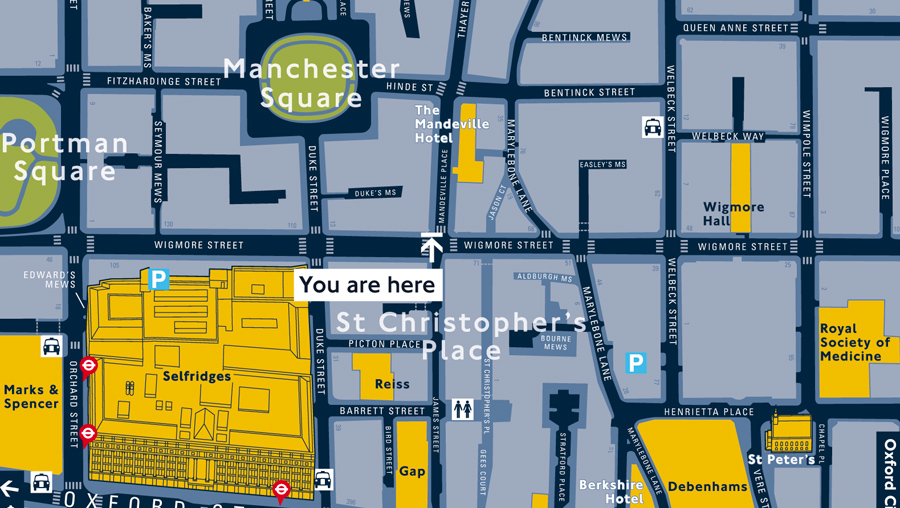

Static signs and maps will still be around for some time, but their role will change. This example map from Legible London reflects this new direction. In contrast to the usual practice, these maps are not displayed with north on top, but are always aligned to the current position of the user. The geocentric map becomes an egocentric map, allowing the user to access the information without the need for mental rotations. This approach can be traced back to studies starting in the 1980s, which proved that You-are-Here maps for emergency routes need to be parallel to the terrain03.

But these maps also have a downside. They clearly show us the spatial relations of the objects in the near surrounding, but they do not place them within a larger context. The map only works at this spot. The user can easily find the next subway station, but he or she can hardly place the objects on a cognitive map of the whole city. And this is the challenge of modern wayfinding systems: How can signs, maps and navigation devices provide simple egocentric directions, but still give the user some kind of large-scale orientation, so we are not completely dependent on external help while navigating?

There is no easy answer for that. Wayshowing (thru directional signage) and orientation (thru physical, electronic and cognitive maps) need to work side by side. Directional signage is purely egocentric. The signs will tell us to go left, right or straight at a decision point, without providing us information of how we move thru the environment in connection to cardinal directions or landmarks along the way. We will reach our target only if the signs work at every decision point. If one part of the way is blocked or we missed a sign, we cannot reach our target, because we have no idea where it actually is. And it will be hard to trace back our route to the starting point, because we just followed endless signs and did not built a large-scale cognitive map of the surrounding. In this article I already gave an example of public transportation networks providing egocentric directions but no orientation within a geocentric frame of reference. This is a typical problem of schematic orientation maps used in malls, office buildings, hospitals, airports and so on. The maps focus on the possible targets (shops, gates et cetera) and the routes between them and leave out information that is actually important for orientation, giving directions and remembering routes. An example of this that made it in the news was the removal of the river Thames on the London subway map. Surely, the river has no relevance to the schedule of the subway network, but it is one of the most essential tools to structure the personal cognitive map of the city of London.

On the right side is a smartphone map of a conference building. The design looks beautiful. No distractions. Just the important halls and routes. The map makes perfect sense for anyone who knows the place. But if you are new to the place: the perfect square doesn’t give much salient cues how to align this image to the current perspective of the user or to a geocentric frame of reference. Pointing out the cardinal directions can be useful for people who know how this building is placed in the environment. Indicating more of the unique design of the building itself or the big river flowing behind and the street and lawn in front of it would probably make the correct alignment of the map very easy for most of the users.

In addition to those orientation cues, people constantly use landmarks to remember a surrounding and to give direction—especially when we speak about decision points along a way. No one would say “turn left in 750 meters” (like an in-car navigation system). We would pick salient features of the environment to aid route descriptions. This can be simple cues like “turn left at the vending machines” or “at the Washington statue”. Wayfinding designers should think about including such landmarks in maps and signs, even if they are no direct part of the network of routes and possible targets.

At best, this is something that urban planners and architects already consider when designing our environments. Well designed buildings are “readable” by themselves without the need for much signage and maps. Architect and environmental psychologist Romedi Passini has written some great books on this subject. Still, reality often looks very different. Take Berlins new and shining main station, built for around 1 billion Euros …

The building has a rather simple symmetrical design which allows users to understand the layout of the building very easily. But what the building won’t provide is orientation! The building has no front or back. Instead there are two very similar exits. The signage will only direct the puzzled tourist to the exit Washingtonplatz or Europaplatz—the names of the surrounding streets/public squares. But which exit should one choose? Like the final stops in my subway lines example, these names are meaningless to tourist and hard to remember, even if you come back to this place several times. It would have been easy to give the station a clear front and back or to equip it with salient landmarks, so every traveler can easily find orientation as soon as he or she exits a train. This could have been done thru architectural design, materials, salient objects, colors, meaningful names and (as a last resort) thru signage. I wonder if these flaws are intentional, so tourist will get lost and spend as much time and money as possible in the shops and restaurants within the building …

- Lynch, Kevin. Managing the sense of a region. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press [↩]

- Dasen & Mishra, Development of Geocentric Spatial Language and Cognition [↩]

- Levine, M. (1982). You-are-here maps: Psychological considerations. Environment and Behaviour, 14, 221–237. [↩]

2011/04/12 at 11:58 AM

Very nice piece of writing - you’ve outlined some key concerns here very well - especially the 21st century bit.

2011/04/14 at 3:25 PM

I agree - great overview of the approach to wayshowing/orientation and the challenges ahead. It’s all about context, culture and expectations, regardless of medium or environment.

2011/04/16 at 10:46 AM

Hi Ralf, thanks for a very well thought-out post. It was interesting to learn that mediaeval maps were drawn with East at the top.

What I find peculiar about current ‘best practice’ in wayfinding map design is how it mixes frames of reference; On the one hand it is egocentric “heads-up”, which means, oriented to reflect the viewer’s perspective.

On the other hand it includes landmark structures drawn in 3D from a bird’s eye view, rather than from the perspective of the person standing on the street.

It’s been clearly shown that 3D illustrations of landmarks assist in orientation, however at street level, we can’t see the roof of Selfridges (as shown on the map above), nor does the roof detail help us in wayfinding.

2011/04/29 at 10:22 AM

very nicely interpreted your thoughts specially 3D illustration of landmarks and 21 century bit ….i loved it